|

|

Major Novels |

| Absalom, Absalom! | As I Lay Dying | A Green Bough | |

| Intruder in the Dust | Light in August | Pylon | |

| The Reivers | Sanctuary | Sartoris | |

| The Snopes Family Trilogy | Soldier's Pay | The Sound and the Fury | The Unvanquished |

|

William Faulkner. Sartoris. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1929.Faulkner drew on his family's past and his Southern heritage for many of his short stories and novels. The first, however, to reveal a direct relationship to his great-grandfather, W. C. Falkner, and his various exploits, is this novel which most critics consider his third "apprentice-novel," following Soldier's Pay (1926) and Mosquitoes (1927). The Sartoris family is one of the more important ones in Yoknapatawpha County. The Old Colonel, John Sartoris, represents a vanished order, one dating from the early to mid-nineteenth century. His world is his plantation home, his slaves, his military action in the Civil War. His son Bayard, the Young Colonel, symbolizes the changing South, a pre-industrial world working out the implications of the lost Confederacy. And the Young Colonel's grandson, Young Bayard, an aviator in World War I, returns after the war unable to attain the standard of Southern manhood exemplified by his great-grandfather, and finding that he must constantly challenge himself through reckless acts to prove that he has the courage to be a Sartoris. |

Many characters and themes of Faulkner's later novels and stories have their origin in Sartoris: the Snopes family, the town of Frenchman's Bend, the unnatural love between a brother and sister, the McCallum family living at one with the natural world, and the conflict between two modes of behavior and social codes represented by the Sartoris and Snopes families. Some details are introduced but not developed. Young Bayard's malaise as a product of the fatality of Southern heritage is not fully explained. Critic Irving Howe described Sartoris as being "a notebook strewn with bits and pieces for a novel still unwritten... the Yoknapatawpha world is not yet seen distinctly...the characteristic tensions ...begin to emerge, but [are] still incipient and undefined." But for all of this, Sartoris is Faulkner's first extended attempt to discover and mold Yoknapatawpha material. It led directly to the creation of his finest novel, The Sound and the Fury, and provided inspiration for the whole, multi-generational society that Faulkner constructed in his books over the next thirty years. It is the only Faulkner title published by Harcourt, Brace, who issued it in a lot of 1,998 copies. | |

William Faulkner.The Unvanquished. New York: Random House,1938.Nine years after the publication which first introduced the Sartoris family, Faulkner published this novel which fills in many of the details surrounding the nineteenth-century family members. Concerned primarily with the Young Colonel Bayard, the son of the eldest John Sartoris, the novel traces his rise to maturity and true courage. The story begins when Bayard and his slave companion, Ringo, are twelve years old and the defeat of the South has been assured. The story ends when Bayard is twenty-four and must make a decision whether to perpetuate the code of revenge or to break the chain of violence that had in the past caused the deaths of his male relatives. The novel consists of seven chapters, the first six published earlier as separate stories, but revised for use in the novel. The seventh, "An Odor of Verbena," was written specifically to demonstrate how Bayard makes the moral decision not to kill and finds the courage to face his father's murderer unarmed. It is a stance that his grandson (Young Bayard in Sartoris, approximately forty-three years later) would be unable to take. The decline of the old family traditions would by then be about complete. Even though the newest member, the infant Benbow Sartoris, is yet to prove himself, he is the child of troubled and weak parents, and his future must merge somehow with that of the South in the mid-twentieth century. |

|

|

William Faulkner. The Sound and the Fury. New York: Jonathan Cape and Harrison Smith, 1929.The Sound and the Fury, William Faulkner's fourth novel, was published on October 7, 1929. It is his masterpiece, a work which most critics consider to be one of the great tragic novels of the twentieth century. In the words of one scholar, Melvin Backman, it is the novel in which Faulkner . . . proved himself a master in his command of a difficult technique, in his control of language, and in the highly original organization of his material. . . [He] showed a keen ear for the sound of people's voices and an even keener sensitivity to the quality of their thoughts and feelings . . . [demonstrating] a remarkable power of characterization. This assessment applies to the book published not more than nine months after the "apprentice" writing of Sartoris. He began it as a short story, tentatively called "Twilight," which very quickly became too small a vehicle for the tale Faulkner was imagining. The story of children being sent outside to play because they were too young to be told what was going on inside developed into a stream-of-consciousness novel with four characters each telling his version of the events that caused the demise of yet another old Southern family, this time the Compson family. |

When the novel first appeared, the reviews were mixed. Some readers could not get beyond the strange surface and structure. This limitation caused critic Winfield T. Scott to assure his readers that the novel was "tiresome," full of "sound and fury--signifying nothing." For the first fifteen years sales totaled just over 3,300 copies. By 1946 when the novel was reprinted, however, scholars were beginning to reassess its significance. Today it is a classic of modern literature and an abundance of criticism exists. It is recognized as more than just the story of another doomed Southern family. It is a study of alienation and the destruction of the bridge between the self and society. | |

William Faulkner. Sanctuary. New York: Jonathan Cape and Harrison Smith, 1931.Faulkner was incredibly productive during the years of 1927 to 1931. Between the time he finished Flags in the Dust in September 1927 and the time he read galley proofs for Sanctuary in November 1930, Faulkner wrote Sanctuary and As I Lay Dying, revised the Quentin Compson section of The Sound and the Fury, and sent out to publishers at least twenty-seven short stories. Faulkner said, at the time, that he wrote Sanctuary to make money, hoping that his shocking story would find a publisher and sell, perhaps even 10,000 copies. He probably did need money and he may have written quickly (he claimed he wrote the book in three weeks). But his manuscript at the University of Virginia reveals as much struggle with this text as with his most difficult work. And when the galleys arrived a year and a half after the initial writing, he revised again, very heavily. The result is a highly serious work, an intense analysis of evil. The critic Noel Polk says that it is "a remarkable and highly sophisticated blend of Eliot, Freud, Fraser, mythology, local color, and even ‘current trends' in hard-boiled detective fiction." |

|

|

William Faulkner. As I Lay Dying. New York: Jonathan Cape and Harrison Smith, 1930.Critic Melvin Backman summarizes Faulkner's progression as a writer and artist during the extremely busy years of 1929 and 1930. He describes a pattern in the changing character of Faulkner's sick heros: The vague guilt and despair of Bayard Sartoris evolved into the specific obsession of Quentin Compson and then into the futility of Horace Benbow (Sanctuary). That Horace's sense of frustration is not as extreme as Bayard's or Quentin's -- Horace did not commit suicide and did not make an attempt to struggle against his society -- suggests some lessening of the malaise. Yet all three novels -- Sartoris, The Sound and the Fury, and Sanctuary -- are dominated by the feeling of alienation. As I Lay Dying breaks from this absorption with the isolated hero. It is instead a study of community, simple country folk (the Tulls, Armstids, and Bundrens), that is almost comic, and certainly reflective of some faith in humanity. The central characters are human beings, more complex than the symbols of evil, estrangement, and post-World-War-I despair that had been important foci in the previous novels. |

Each character narrates his or her own version of the events, in this regard similar to The Sound and the Fury. | |

William Faulkner. Light in August. New York: Harrison Smith & Robert Haas, 1932.In the summer of 1931 Faulkner began work with a new story he entitled "Dark Horse." That title changed abruptly, however, when one day in August his wife Estelle commented on how different light in August is from any other time of the year. Faulkner said later that "I used it because in my country there's a peculiar quality to light and that's what that title means." The novel was difficult to write. The original manuscript is one of Faulkner's longest, full of false starts, marginal inserts, cancellations, discarded sheets, and paste-ons. It began first as the story of Reverend Gail Hightower; then several attempts brought other minor characters into prominence; but eventually the novel became the story of Joe Christmas, a solitary figure who, in the words of Joseph Blotner, "shows the terrible effects of the vicious prejudice and vindictive religiosity visited upon him from earliest childhood." Faulkner sent the manuscript to his agent Ben Wasson and then to his publisher Harrison Smith. Smith's association with Jonathan Cape was falling apart, moving from receivership to liquidation. Smith found another partner, however, and by late summer of 1932 he and Robert Haas had the galleys ready to proof. The novel was published on October 6, 1932. |

|

|

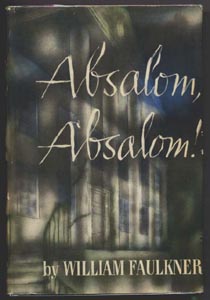

William Faulkner. Absalom, Absalom! New York: Random House, 1936.Seven years passed between the publication of The Sound and the Fury and Absalom, Absalom! Faulkner had not worked in depth with the Compson family during that time, but many stories drew on one or more members of the family, and as early as fall 1933, Faulkner was thinking about the plot of Absalom, Absalom! He wrote to his publisher Harrison Smith: I believe that I have a head start on the novel . . . The one I am writing now will be called DARK HOUSE or something of that nature. It is the more or less violent breakup of a household or family from 1860 to about 1910. It is not as heavy as it sounds. The story is an anecdote which occurred during and right after the civil war; the climax is another anecdote which happened about 1910 and which explains the story. Roughly, the theme is a man who out- raged the land, and the land then turned and destroyed the man's family. Quentin Compson, of The Sound & Fury, tells it, or ties it together . . . I use him because it is just before he is to commit suicide because of his sister, and I use his bitterness which he has projected on the South in the form of hatred of it and its people to get more out of the story itself than a historical novel would be. To keep the hoop skirts and plug hats out, you might say. |

Various obligations delayed the development of these plans, but by mid-1934, Faulkner had decided on the final title (Absalom, Absalom!) and the theme was expanding: "the story is of a man who wanted a son through pride, and got too many of them and they destroyed him . . ."The story was difficult, however, and again Faulkner needed to turn to other projects, this time the novel Pylon and several short stories using similar characters and themes. By spring 1935, he returned to the novel, writing steadily, but with some unavoidable and painful interruptions, such as the death of his youngest brother and time in Hollywood writing movie scripts. It was a year before the revised pages reached Hal Smith, and October 1936 before the book was finally published. It was, however, worth the wait. Smith & Haas had joined as partners with Random House, and there was more money to produce a fine publication. This trade edition copy reveals a lovely cloth binding stamped in red and gold with an excellent jacket depicting the doomed plantation mansion. | |

William Faulkner. Intruder in the Dust. New York: Random House, 1948.The decade of the 1940s was less prolific for Faulkner. Large writing projects were slow in developing, and much of his time was spent with short stories, filmscripts, and responding to World War II. But there was one idea for a story that persisted. As early as 1940, Faulkner mentioned in a letter to his publisher that he had in mind "a blood-and-thunder mystery novel, original in that the solver is a negro, himself in jail for the murder and is about to be lynched, solves murder in self defense." He finally got around to writing this story in January 1948. By April when he finished the revisions, the story had become a full-length novel, and the whodunit mystery had developed into "a pretty good study of a sixteen-year-old boy who overnight became a man" by doing his part to help save the life of the aging prisoner, Lucas Beauchamp. Faulkner told his agent that the novel deals again with the relationship between black and white, "specifically . . . the premise being that the white people in the south, before the North or the government or anyone else, owe and must pay a responsibility to the Negro." The boy, Chick Mallison, learns this lesson as his perception of Lucas as a man changes and he becomes more aware of the plight of the black people in Yoknapatawpha County. The passage shown here describes the end of a meeting between Lucas and Chick when Chick realizes that no one else will help Lucas and that he must go to the cemetery himself and dig up the body to find out what kind of bullet caused death. As he accepts this responsibility, he also begins to understand why he must do so. |

|

|

The Snopes Family TrilogyPublished as a set in the late 1960s and 1970s by Vintage Books.William Faulkner. The Hamlet. New York: Random House, 1940.The first of the Snopes trilogy, The Hamlet, depicts the beginning of Flem Snopes's systematic rise to wealth and power by means of treachery and cunning. He moves from being a poor white tenant farmer to clerk in the general store of Frenchman's Bend. The Snopes clan plays a significant role in Faulkner's Yoknapatawpha saga.They are poor white trash, sharecroppers competing for an economic foothold with newly-freed slaves.They are ruthless, predatory, amoral, devouring, and above all self-serving, and as a group Faulkner depicts them like an infestation of snakes or rats, termites, army ants, or weevils. |

Faulkner devoted three novels to these unpleasant inhabitants, the first published in 1940 and the last in 1959.He had a Snopes book in mind, however, as early as 1926 with the short story "Father Abraham,"and then in 1931 with another version, "Spotted Horses." These characters and the extended family would not go away, and over the years they figure in many of Faulkner's works:the bank teller who writes obscene letters to Narcissa Benbow in Sartoris, the senator in the Memphis brothel scenes in Sanctuary, and Ab Snopes in The Unvanquished, who collaborates in mule thieving and trading. | |

|

William Faulkner.Soldier's Pay. New York: Boni & Liveright, 1926.One of Faulkner's passions throughout his life was flying. As a boy he built an airplane made out of beanpoles, slats, baling wire, wrapping paper, and paste, and filled many pages with drawings of goggled men in fragile flying machines.Then during World War I, after a fair amount of conniving and deception, he managed to be accepted into the Canadian Royal Air Force, training to become a pilot for the Western Front. He studied aircraft rigging, theory of flight, aerial navigation, bomb raiding, reconnaissance, and aircraft specifications, and even logged in enough flight time to claim (in a letter to his mother) at least four hours of solo flying, all before the Armistice of November 11, 1918, put an end to his dream of participation in aerial, man-to-man combat. His desire to fly did not abate, however.In 1920 he arranged for a few lessons from a poker-playing buddy, in 1925 he experienced "looping-the-loop in a bucket seat and open cockpit over the Mississippi," and in 1933, he began formal instruction with Captain Vernon Omlie, a veteran of Army flying and extensive barnstorming.This last association led to Faulkner's purchase of his own plane, a Waco F biplane. He enjoyed a period of regular flying, sharing the experiences especially with his brothers and other flyers and veterans who engaged in the talk of "hangar flying." |

Numerous stories, poems, and some novels drew on this avocation. The earliest of the long works was Soldiers Pay, his first published novel. Originally titled Mayday, Faulkner began in the spring of 1925 by pulling together a few stories he had already written, and working to expand them and develop a connected extended narrative.The story tells of the return home of a wounded and dying soldier, Lieutenant Donald Mahon, accompanied by Yaphank (i.e., boisterous and engaging Private Joe Gilligan) and war widow Margaret Powers. When the novel appeared in February 1926 the reviews were surprisingly favorable for a first novel.Critics called it "an extraordinary performance,"the "most noteworthy first novel of the year,"and a book written with "hard intelligence as well as consummate pity." By May, nearly all of the 2,500-copy first printing had sold. | |

William Faulkner.Pylon.New York:Harrison Smith and Robert Haas, 1935.The novel which most directly reflects Faulkner's love of flying is Pylon.It draws particularly on his enthusiasm for the skill, daring, and wild lifestyle of barnstorming aviators.His flying instructor, Vernon Omlie, was one of them.After his Army years, Omlie and his wife put on air shows, "with Phoebe as wing walker, swinging from one plane to another, then jumping, cutting away her parachute and falling free until she popped open a second one"(Blotner, Faulkner: a Biography).They became part of a flying circus, and then started a flying school in Memphis, where Faulkner went for his lessons. The Omlies introduced Faulkner to a way of life which fascinated him. He accompanied them whenever possible to air shows, and loved to listen to the stories of other flyers.Although he never enjoyed aerobatics, he did solo for enough hours, mostly flying straight and level, to earn his pilot's license in December 1933. Faulkner wrote Pylon quickly during the fall of 1934.The changes to the galleys in January were minimal, and by March 1935 it was published. It concerns five principal characters--a pilot and his wife, a jumper, a mechanic, and a reporter.All are based on real people Faulkner had observed in the bizarre world of dare-devil flyers and racers. He presents them with admiration and respect while recognizing that they were "outside the range of God, not only of respectability, of love, but of God too." |

|

|

William Faulkner.A Green Bough.New York:Harrison Smith and Robert Haas, 1933.Faulkner wrote poetry on and off throughout his life, even while most of his energies were directed toward prose.As he developed as a realistic novelist, so did he change as a poet.In this second collection, published nine years after The Marble Faun, the poems are more eclectic and varied.There are ballad-style poems reminiscent of his teenage writing, experimental ones suggestive of e. e. cummings, short lyrics, and sonnets. The opening poem, called "The Lilacs" though untitled in this publication, was written years earlier, probably in late 1919 or early 1920 when his experiences with the Canadian Air Force and aviation were still fairly fresh.It is a dramatic monologue with the central character being a maimed aviator who remembers his night raids over Mannheim and the May morning when he was shot down.It is effective in large part because of the visual imagery and the realistic setting conveyed through the wandering mind and impaired vision, but keen hearing, of the soldier. A Green Bough was published in both limited and trade editions, although no priority has been determined. Our copy of the limited edition is number twenty-three of 360 copies, all signed by the author.The engravings are by Lynd Ward. |

William Faulkner.The Reivers.New York:Random House, 1962.After the last novel in the Snopes trilogy was published, readers, and maybe even Faulkner himself, might have thought that the creative years were over.But there was still one more novel to write, "a sort of Huck Finn" that Faulkner had first mentioned as early as 1940. It began during the summer of 1961 with three chapters entitled "The Horse Stealers: a Reminiscence." Faulkner gave the first several chapters to Joseph Blotner to read, but soon he was writing quickly with an energy he had not displayed in writing for some years.By the end of August he had the typescript of his nineteenth novel ready for mailing. During revisions, the biggest change was the title. He decided to call the protagonists "reavers"or people who rob or plunder. Later he changed the spelling to an archaic Scottish version ("reivers") which he felt had "a more ‘swashing' sound." |

|

The story carries many similarities to Faulkner's own family, and it could be he had in mind one more lesson he wanted to leave with his own grandchildren.The novel begins, "Grandfather said,"and the tale then proceeds as a reminiscence by Grandfather about events that happened in 1905.The fictional characters resemble Faulkner's brothers, his father who owned a livery stable, and his grandfather who was a banker. Even Boon Hogganbeck and Ned McCaslin show similarities to particular employees and servants whom Faulkner would have known. The list of books on the page facing the title page is an impressive legacy, and must have pleased Faulkner at sixty-four.He had more and more been talking of death, and finally succumbed on July 6, 1962. He is buried in Oxford, Mississippi, in the Falkner/Faulkner family plot. | |