Three Urbanisms: New, Everyday and Post

From: University of Michigan | By: Douglas Kelbaugh

You may have heard of New Urbanism, a movement that promotes neo-traditional, neighborhood-based urban design. It has enjoyed meteoric success in the American media. However, it is far from the centerline of either the academic or the real estate development world. Despite successful greenfield projects, those built on open farmland, such as the Kentlands outside Washington and Harbor Town in Memphis, conventional suburban development continues to envelop the American metropolis with its cul-de-sac subdivisions and big box retail. The metro region is still spreading out at a rate considerably faster than population is growing.

You may have heard of New Urbanism, a movement that promotes neo-traditional, neighborhood-based urban design. It has enjoyed meteoric success in the American media. However, it is far from the centerline of either the academic or the real estate development world. Despite successful greenfield projects, those built on open farmland, such as the Kentlands outside Washington and Harbor Town in Memphis, conventional suburban development continues to envelop the American metropolis with its cul-de-sac subdivisions and big box retail. The metro region is still spreading out at a rate considerably faster than population is growing.

And conventional urban development and redevelopment are fast changing our downtowns into entertainment, tourist, convention, sports, or office centers. Philadelphia, for instance, has recently converted five downtown office buildings into tony hotels. These profound changes are happening piecemeal, without much input from urban designers and planners in general, much less from New Urbanist practitioners and writers. New Urbanism enjoys little and usually begrudging respect in academia, especially in most schools of architecture where avant-garde theory continues to dominate. And yet it has been described by Paul Goldberger of the New Yorker as the most important design movement of the baby boomer generation.

Beyond the conventional "market" urbanism that is willy-nilly changing the face of American downtowns and suburbs, there are at least three self-conscious schools of urbanism: New Urbanism, Everyday Urbanism and what I call Post Urbanism. These three cover most of the cutting edge of theoretical and professional activity in architecture and urbanism. All three are inevitable and necessary developments in and of the contemporary human condition.

New Urbanism

New Urbanism is idealistic, even utopian. It is utopian because it aspires to a social ethic that builds new communities and repairs old communities in ways that attempt to equitably mix people of different income, ethnicity, race and age, and because it promotes a civic ideal that mixes land of different uses and buildings of different architectural types. It sponsors public architecture and public space that attempt to make citizens feel they are part, even proud, of a culture that is more significant than their individual, private worlds and a natural ecology that might even be sustainable.

New Urbanism eschews the physical fragmentation and functional compartmentalization of modern life and tries "to make a link between knowledge and feeling, between what people believe and do in public and what obsesses them in private" (T. Zeldin, An Intimate History of Humanity). It maintains that there is a structural relationship between social behavior and physical form, although the connection can be subtle and elusive. It posits that good design can have a measurably positive effect on one's sense of place and community, which it holds are essential to a healthy, sustainable society. The basic model is a compact, walkable city with a hierarchy of private and public architecture and open spaces that are conducive to face-to-face social interaction, including background housing and private yards as well as foreground civic and institutional buildings, squares and parks.

Everyday Urbanism is not as utopian as New Urbanism. Nor is it as tidy. It celebrates and builds on everyday, ordinary life and reality, with little pretense about the possibility of building a perfectible or ideal environment. Its proponents are open to and incorporate "the elements that remain elusive: ephemerality, cacophony, multiplicity and simultaneity" (J. Kaliski, Everyday Urbanism). This grassroots openness to populist informality makes Everyday Urbanism conversational as opposed to inspirational. Unlike New Urbanism, it downplays the relationship between physical design and social behavior. For instance, it celebrates the way indigenous and migrant groups informally respond in resourceful and imaginative ways to their ad hoc conditions and marginal spaces. Appropriating space for commerce in parking and vacant lots, as well as private driveways and yards for garage sales, is urban design by default rather than by design. Vernacular and street architecture in vibrant, ethnic neighborhoods like the barrios of Los Angeles, with public markets rather than chain stores, and street murals rather than civic art, are championed. Everyday urbanism could be confused with conventional real-estate development but it is more intentional, ideological and democratic than the generic "product" that mainstream bankers, developers and builders supply to an anonymous market.

Post Urbanism, which is hot among design professionals and academicians, is heterotopian and sensational. It is sometimes called landscape urbanism or infrastructure urbanism, which also points to a post-structuralist view of the world. It welcomes disconnected, hypermodern buildings and shopping mall urbanism. It argues that shared values or metanarratives are no longer possible in a world that is increasingly fragmented and composed of isolated zones of the "other" (e.g. the homeless, the poor, criminals, minorities) as well as mainstream zones of consumers, Internet surfers, and free-range tourists. Outside the usual ordering systems, these liminal zones of taboo and fantasy and these commercial zones of unfettered consumption are viewed as liberating because they allow "for new forms of knowledge, new hybrid possibilities, new unpredictable forms of freedom" (Ellen Dunham-Jones, personal correspondence). New Urbanist communities based on physical place and propinquity are claimed to be stultifying, repressive, and no longer relevant in light of modern technology and telecommunications.

Post Urbanism attempts to wow an increasingly sophisticated consumer of the built environment with ever-wilder and more provocative architecture and urbanism, like architect Frank Gehry's Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain. Like Modernism, its architectural language is usually abstract with little reference to surrounding physical or historical context. It also continues the modernist project of avant-garde shock tactics, no matter how modest the building site or program. It is sometimes hard to know if it employs shock for its own sake or whether the principal motive is to inspire genuine belief in the possibility of changing the status quo and of resisting controls and limits that are thought to be too predictable, even tyrannical. Gehry describes his exuberant insertions into the city as examples of open, democratic urbanism, despite the fact they usually ignore or overpower local discourse. His projects are usually self-contained and microcosmic, with little faith in the work of others to complete the urban fabric, even the dynamic, fragmented one that Post Urbanists like. Signature buildings, which are typically more self-referential than contextual, and sprawling auto-centric cities like Atlanta, Houston and Las Vegas, are held up as models, although the very idea of model might be rejected outright by Post Urbanists.

Sensibilities, methodologies and outcomes

The differences in these three architectures and urbanisms probably start with the designer's aesthetic sensibilities, which are arguably more basic than design values. Sensibilities often come down to early experiences and memories, such as toilet training and childhood play. They are less conscious and harder to change than acquired knowledge and learned values. How messy and complex a world designers can tolerate is probably harder wiring than how much injustice they can tolerate or how many problems they can justify passing on to future generations. Where designers fit on the spectrum of these three paradigms may ultimately have to do with whether they prefer in the gut to spend time, for instance, around the grand monuments and boulevards of nineteenth-century Paris or in the medieval streets and buildings of its Marais district or in the free-standing high-rise complex of La Defense, its twentieth-century office complex. (They may, in fact, enjoy hanging out in more than one of these places, depending on mood, time of day, etc., but a designer's portfolio rarely if ever spans this range.) Social and ethical values of course temper these visceral design sensibilities, but the gut often prevails over the mind.

These three urbanisms utilize different methodologies. New Urbanism is the most precedent-based. It tries to learn and extrapolate from the most enduring architectural types, as well as historical examples and traditions as they intersect with contemporary environmental, technological, social, economic and cultural practices. It is also the most normative, often drafting prescriptive codes rather than proscriptive zoning. Coherence, legibility and human scale in architecture and urbanism are highly valued, as is diversity of uses and users.

New Urbanism has a curious pedigree. It's a mix of architecture, urban design and urban planning conceived and popularized almost exclusively by architects. The movement has grown out of two intellectual strains in America. One wing, represented by liberal Peter Calthorpe and his West Coast colleagues, is environmentalism. Peter and I and others came out of the passive solar movement (1975-85), which evolved, for me anyway, into an interest in regionalist design and then into regional design, including city and regional planning. The other wing, represented by politically conservative Andres Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk of Miami and of European sensibility, grows more out a traditional architectural and urban formalism.

One from the left and one from the right, they independently and happily came to the same conclusion: America needed to reject the modernist paradigm of specialized land use with specialized buildings designed and developed by specialists for specialized communities. Rather, it needed mixed use, mixed income, mixed ethnicity, neighborhood-based, walkable, transit-oriented communities, more like the pre-automobile cities of our grandparents. They also agreed on the finitude of the world; the environmentalist wing believed in finite natural resources and the formalist wing believed in finite architectural and urban composition. Planning, as well as politics, can make for strange bedfellows.

One from the left and one from the right, they independently and happily came to the same conclusion: America needed to reject the modernist paradigm of specialized land use with specialized buildings designed and developed by specialists for specialized communities. Rather, it needed mixed use, mixed income, mixed ethnicity, neighborhood-based, walkable, transit-oriented communities, more like the pre-automobile cities of our grandparents. They also agreed on the finitude of the world; the environmentalist wing believed in finite natural resources and the formalist wing believed in finite architectural and urban composition. Planning, as well as politics, can make for strange bedfellows.

Everyday Urbanism is the most populist of the three urbanisms, with the designer seen as an empirical student of the common and popular rather than the ideal and pure.

It grows out of both the community design movement and to a lesser extent the pop art movement. The design professional has fewer conceits. She is more of a co-equal participant in the public dialogue with the local citizens. Citizen participation is the most open-ended and democratic of the three. It is less normative and doctrinaire than New Urbanism, because it is more about celebrating and intensifying existing, everyday conditions, such as public markets and street life, than overturning them and starting over with a different model. It is also the most modest and compassionate of the paradigms. If the New Urbanist romanticizes a mythic past, the Everyday Urbanist overestimates the mythic aspect of the ordinary and commonplace.

It grows out of both the community design movement and to a lesser extent the pop art movement. The design professional has fewer conceits. She is more of a co-equal participant in the public dialogue with the local citizens. Citizen participation is the most open-ended and democratic of the three. It is less normative and doctrinaire than New Urbanism, because it is more about celebrating and intensifying existing, everyday conditions, such as public markets and street life, than overturning them and starting over with a different model. It is also the most modest and compassionate of the paradigms. If the New Urbanist romanticizes a mythic past, the Everyday Urbanist overestimates the mythic aspect of the ordinary and commonplace.

Post Urbanism claims to accept and express the techno-flow of a global world, both real and virtual. It is experimental rather than normative and likes to subvert design and zoning codes and convention. Post Urbanists don't engage the public as directly in open dialogue because they feel the traditional "polis" is obsolete and its civic institutions too calcified to promote new possibilities. They tend rather to operate as "lone geniuses" contributing a monologue, often an elitist and egocentric one, that is directed to the media and the marketplace. Architects like Rem Koolhaas, the famous Dutch provocateur, claim there is no longer any hope of achieving urban coherence or unity. Their architecture is internally consistent, elegantly so in many cases, but demonstrates little interest in weaving or reweaving a consistent or continuous urban or ecologic fabric over space and time. Projects tend to be X-L (extra-large), denatured, bold, esoteric and overwhelming to their contexts. If the New Urbanist tends to hold too high the best practices of the past and the Everyday Urbanist overrates a prosaic present, the Post Urbanist is over-committed to an endlessly exciting and needlessly audacious future.

The three paradigms lead to very different physical outcomes. New Urbanism, with its Latinate clarity and order,  achieves the most aesthetic unity and social community as it mixes different uses at a human scale in familiar architectural types and styles. Its connective grids of pedestrian- and car-friendly streets look better from the ground than the air, from which they can sometimes look formulaic, baroque and overly symmetrical. (Ironically, the curvy cul-de-sacs of suburbia look elegant from the air, in spite of their functional shortcomings on the ground.) Everyday Urbanism, which is the least driven by aesthetics has trouble achieving beauty or coherence, day or night, micro or macro, but is egalitarian and lively on the street. Post Urbanist site plans always look the most exciting, with their laser-like vectors, fractal geometries, sweeping arcs and high-speed circulatory systems. However, they are over-scaled and empty for pedestrians. Tourists in rental cars experiencing the architecture and urbanism through their windshields are a better-served audience than residents for whom there is little human-scale nuance and architectural detail to reveal itself over the years. Local citizens become tourists in their own city, just as tourists become, conversely, citizens of the world.

achieves the most aesthetic unity and social community as it mixes different uses at a human scale in familiar architectural types and styles. Its connective grids of pedestrian- and car-friendly streets look better from the ground than the air, from which they can sometimes look formulaic, baroque and overly symmetrical. (Ironically, the curvy cul-de-sacs of suburbia look elegant from the air, in spite of their functional shortcomings on the ground.) Everyday Urbanism, which is the least driven by aesthetics has trouble achieving beauty or coherence, day or night, micro or macro, but is egalitarian and lively on the street. Post Urbanist site plans always look the most exciting, with their laser-like vectors, fractal geometries, sweeping arcs and high-speed circulatory systems. However, they are over-scaled and empty for pedestrians. Tourists in rental cars experiencing the architecture and urbanism through their windshields are a better-served audience than residents for whom there is little human-scale nuance and architectural detail to reveal itself over the years. Local citizens become tourists in their own city, just as tourists become, conversely, citizens of the world.

Everyday Urbanism may make sense in developing countries where global cities are mushrooming with informal squatter settlements that defy government control and planning, and where underserved populations simply want a stake in the economic system and the city. But it doesn't make sense in the cities of Europe, where a wealthy citizenry has the luxury of fine-tuning a mature urban fabric and punctuating it with commercial and institutional buildings that can be vivid counterpoint. In North American cities, which lack the continuous fabric of European cities and are underprogrammed and even empty, New Urbanism makes sense. In the ecology of cities, development in the third world and in poor American neighborhoods represents early successional growth, the beginnings of a forest. Middle-aged North American cities are trying to thicken their stand of mid-successional growth. European cities are more like climax or late successional forests, with glorious elm and beech trees, where there is little room for growth except in clearings carefully made for experimental species.

Everyday Urbanism is too often an urbanism of default rather than design, and Post Urbanism is too often an urbanism of sensational, trophy buildings in an atrophied public realm. We can build a more physically ordered commons than Everyday Urbanism promises and a more emancipatory commons than Post Urbanism offers. Although Europe may hanker for Post Urbanism and the developing world may embrace Everyday Urbanism, the typical American metropolis needs and would most benefit from New Urbanism at this point in its evolution. It is the responsible if less glamorous middle path, which can and should be pursued as passionately as the more provocative extremes. It may not be an absolute or ultimate fix (indeed, it will eventually ossify and lose its meaning and value as it runs the usual historical course from archetype to type to stereotype), but it is far superior to what passes for new brownfield (old, polluted industrial sites), grayfield (failed suburban malls and parking lots), and greenfield communities in America today.

Civitas: the public realm

Without community, without civitas, we are all doomed to private worlds that are selfish and loveless. As our society becomes more privatized and our culture more narcissistic, the need and appetite to be part of something bigger than our individual selves grow. Organized religion and individual spiritual development answer this need for many people. For some people, however, belonging to a community or "polis" may be the highest expression of this spiritual need. And for all members of society, there is the need to be part of some social structure. People are social animals, and our need to share and to love makes community a sine qua non of existence. On the other hand, humans also have a fundamental need to express themselves as individuals, to individuate themselves psychologically and socially, even to excel and rise above the crowd. A community must simultaneously nurture both a respect for group values and a tolerance for individuality, even eccentricity. This is the paradox of community that will forever require readjustments.

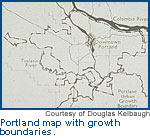

Community must deal with the full range of human nature, including its own dark side. If it projects its own dysfunction and pathologies onto an outside enemy or stigmatized minority, it has not fully faced itself and is in collective denial. More typically, the unity in community is bought at the price of identifying enemies, who are sure to return the favor. Enemies will get even some day, as the chain reaction of intolerance and injustice is perpetuated. If this dialectic is an inevitable part of the human condition, the question arises as to what is the most hospitable scale for social harmony and political unity and the least hospitable scale for hatred and enmity. It begs a deeper question: at what scale are civitas, justice and brotherly love best fostered? Ancient Greek philosophers suggested that 5,000 citizens was an optimum size for a polis. (With wives, children and slaves, the total number must have been more like 25,000.) New Urbanism presents the case that the neighborhood of a half mile on a side and the metropolitan region are the two most sensible and equitable scales for community to thrive and for governance, planning and taxation to be effective in the metropolis. Portland, Oregon, has become the poster child of regional planning and growth management with its famed metropolitan growth boundaries.

Community must deal with the full range of human nature, including its own dark side. If it projects its own dysfunction and pathologies onto an outside enemy or stigmatized minority, it has not fully faced itself and is in collective denial. More typically, the unity in community is bought at the price of identifying enemies, who are sure to return the favor. Enemies will get even some day, as the chain reaction of intolerance and injustice is perpetuated. If this dialectic is an inevitable part of the human condition, the question arises as to what is the most hospitable scale for social harmony and political unity and the least hospitable scale for hatred and enmity. It begs a deeper question: at what scale are civitas, justice and brotherly love best fostered? Ancient Greek philosophers suggested that 5,000 citizens was an optimum size for a polis. (With wives, children and slaves, the total number must have been more like 25,000.) New Urbanism presents the case that the neighborhood of a half mile on a side and the metropolitan region are the two most sensible and equitable scales for community to thrive and for governance, planning and taxation to be effective in the metropolis. Portland, Oregon, has become the poster child of regional planning and growth management with its famed metropolitan growth boundaries.

Americans have been quick to exchange the more raw and uncomfortable sidewalk life of the inner city neighborhood for the easy and banal TV life of the suburban family room. We have been too quick to give up the public life that American cities have slowly mustered in spite of a long legacy of Jeffersonian rural yeomanry and anti-urbanism. It has been our good fortune that immigrants from countries with strong public realms (and cities where the wealthy citizens

Americans have been quick to exchange the more raw and uncomfortable sidewalk life of the inner city neighborhood for the easy and banal TV life of the suburban family room. We have been too quick to give up the public life that American cities have slowly mustered in spite of a long legacy of Jeffersonian rural yeomanry and anti-urbanism. It has been our good fortune that immigrants from countries with strong public realms (and cities where the wealthy citizens

live downtown rather than at the periphery) have imported urban and ethnic values for which we are much the richer. But many European immigrants have wanted to leave the public life behind. Indeed, the pioneers of Modernism in Europe came out against traditional urban streets and the messy complexity they sponsor. The most heroic of all twentieth-century European architects, Le Corbusier, led the battle for a more "rational" separation of vehicles and pedestrians in a new urban vision that spread to and across America.

live downtown rather than at the periphery) have imported urban and ethnic values for which we are much the richer. But many European immigrants have wanted to leave the public life behind. Indeed, the pioneers of Modernism in Europe came out against traditional urban streets and the messy complexity they sponsor. The most heroic of all twentieth-century European architects, Le Corbusier, led the battle for a more "rational" separation of vehicles and pedestrians in a new urban vision that spread to and across America.

African-Americans, the group brought to America most forcibly and most unfairly, have often maintained a strong and rich street life, as have Latinos. But European Americans have continued to flee the public realm, most recently from public city streets to the gated subdivisions of affluent, second ring suburbs. They have taken the money with them and the best schools, without which there cannot be healthy community. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development's Hope VI program, which is inspired by New Urbanism, has begun to dramatically reverse the inner city public housing projects, which have warehoused low-income residents, primarily African-Americans, in high-rise towers. They are being torn down and replaced with low income street-oriented town homes.

Few humans would deny the value of civitas, as well as mutual respect and tolerance. But many contemporary critics question the notion of traditional community. They posit that communities of interest, including ones enabled by modern electronic communications, have supplanted what used to be communities of propinquity and place. This is not a new notion in the US; as de Tocqueville observed: "Americans of all ages, all stations of life, and all types of disposition are forever forming associations . . . religious, moral, serious, futile, very general and very limited, immensely large and very minute."

It is an undeniable fact that telecommunications and computers have changed our lives in many ways and will continue to do so at an increasing rate. However, it is not evident that they have reduced our need for physical community. Indeed, living with a computer screen in your face all day and a telephone in your ear, with radio or CD in the background, may increase the appetite for physical community. As the poet and pundit Gary Snyder has said, the Internet is not a community or a commons because you can't hug anyone on it. The World Wide Web may prove antithetical to community by providing anonymous sources with instantaneous access to vast audiences to which they are not accountable.

Never have such hidden voices had such access to such large audiences. Electronic snipers alongside the information highway are not engaging in public discourse, any more than a website can equal an Italian piazza. If anything, electronic communications have increased the human need for traditional neighborhoods with buildings you can kick and neighbors at whom you can wave or frown.

Never have such hidden voices had such access to such large audiences. Electronic snipers alongside the information highway are not engaging in public discourse, any more than a website can equal an Italian piazza. If anything, electronic communications have increased the human need for traditional neighborhoods with buildings you can kick and neighbors at whom you can wave or frown.

There are several ways to go with these weightless invisible electrons, which have no architectural palpability. One way is to accept, embrace and even celebrate their evanescence and flux, trying to make an architecture and urbanism that is transitory and ephemeral. This is the Post-Urbanist city where a physical public realm, indeed the very notion of urbanism, is denied or at least transformed beyond recognition. Both Everyday and New Urbanism are committed to a vibrant, authentic public realm, with face-to-face interaction. Another way is to resist the electronic net as the primary public realm, to build a high quality physical world of buildings, streets, plazas and parks that encourage and dignify human interaction among friends and strangers, rich and poor, black and white, old and young. That is the time-tested strategy that New Urbanism has rechampioned, first with the automobile and now the electron, not to exclude technology but to tame and control it. The law of unintended consequences is strong enough.

Traditional notions of the city and of community and its pubic realm are being challenged by new design ideologies and new technologies. It's confusing and we need to step back, especially in the US, and examine what drives us as designers and as citizens. As designers, are we too enthralled by innovation, or worse, the appearance of innovation? Has this mandate for originality, or worse, for novelty slowly ruined our cities? Is it now turning them into Post-Urban places of entertainment and spectacle? Does Everyday Urbanism, on the other hand, underestimate the value that architectural and urban form can add to our lives? As citizens, are we too seduced by private pleasures and personal conceits to cultivate a rich, coherent, and democratic public realm? In our quest for a new civitas, which New Urbanism can help sponsor, are we prepared, like great cultures before us, for the balance and discipline required? Or will technology, the market, the media and design vanity simply pull us where they want?