A Call for Sustainable Development

From: University of Michigan | By: Thomas N. Gladwin

Many industry leaders and management theorists have considered the economic and technological dimensions of corporate strategy, presenting their ideas as seemingly "value free." Some have examined social issues but relatively few have related the topic to the natural world. Corporate strategists have focused their energies on the instrumental realm of markets and efficient resource allocation, evading the exploration of how strategy relates to ultimate ends (i.e., human fulfillment and community) and ultimate means (i.e., the capacity of the biosphere to support life). They have implicitly assumed that continuous growth and technological progress are inevitable. They have tended to focus on rather proximate matters shaping masterful strategic management, rather than attending to the more systemic, non-linear, large-scale, long-term and slow-motion processes set to shape strategy in coming decades. In this article, I would like to redress the balance.

The biases I have just mentioned are not atypical of management theorists. But a variety of dysfunctions arise when business in general, and strategy in particular, becomes detached from the biosphere, the full human community, and the principles of right conduct in the world. Our strategic sense-making, for example, is channeled away from the fundamental interdependencies (and associated vulnerabilities) that ultimately determine organizational success and survival; our sensitivities are numbed to the moral injunctions, obligations, and accountabilities which stakeholders attach to the "responsible" mastery of strategy; our creative capacity to envision glorious corporate opportunities associated with fulfillment of basic human needs is constrained; and our search for genuine meaning and purpose in this world is impeded if weighty questions like for who, where, when and what purpose are we mastering strategy are discouraged.

This article examines the business case for sustainable development and the leadership challenges that it implies.

Why it matters

Threats to the integrity, productivity and resilience of both our natural and social "life support" systems have been widely highlighted by scientists in recent years (see Figure 1). Well-documented examples include: the over-exploitation of fish stocks, falling water tables on every continent, major rivers running dry, overgrazing and soil erosion.

Concentrations of carbon dioxide are increasing in the atmosphere, global average temperatures are rising, extreme weather events are increasing in frequency and severity, nitrogen overloading is acidifying rivers and lakes, ultraviolet radiation is rising due to stratospheric ozone depletion, and toxic heavy metals and persistent chemicals are building up steadily in organisms and ecosystems.

The earth's forests are shrinking, highly productive wetlands are vanishing especially in coastal areas, coral reefs are dying, natural ecosystems are being lost thanks to exponential rates of land use change, invasions of non-native species are on the rise due to global traffic, and species are being exterminated about a thousand times faster than normal.

The earth's forests are shrinking, highly productive wetlands are vanishing especially in coastal areas, coral reefs are dying, natural ecosystems are being lost thanks to exponential rates of land use change, invasions of non-native species are on the rise due to global traffic, and species are being exterminated about a thousand times faster than normal.

The knee-jerk reaction to such news is typically psychodynamic denial, repression or rationalization. But masters of strategy need to acknowledge that human population growth and growth in resource consumption are altering our planet in unprecedented ways, at a faster pace and on a broader scale than previously. Scientists warn that we are eating up the planet's natural capital, crossing a range of sustainable yield thresholds, and fomenting conflict, within and across generations, over the growing scarcity of natural resources.

As shown in Figure 1, steady deterioration in the Earth's biophysical health and the stagnant or falling quality of life for a majority of humans are closely connected. A swelling global population, persistent deprivation and growing social disintegration are just some of the problems. United Nations reports say the world's human population, after soaring from 1.6 billion in 1900 to a little over 6 billion today, is projected (despite lower fertility rates) to reach 8 billion in 2020, and perhaps stabilize at around 9 billion to 10 billion by 2050. In the time it takes to read this article, the planet's net population will have risen by 1800 people. An estimated 350 million couples still have no access to family planning.

Population pressures and the associated economic/ecological/political decline fuels internal and cross-border migration. Rural to urban migration is producing mega-cities, especially in the developing world. Medical experts warn that the epidemiological environment is deteriorating. Old diseases like tuberculosis are resurgent and new ones, such as HIV/AIDS, emergent.

Global data on persistent human deprivation are even more distressing. An estimated 37,000 infants will die today from poverty-related causes; more than 260 million children are out of school at the primary and secondary levels; 840 million people are malnourished; 850 million adults remain illiterate; 880 million people lack access to health services; 1 billion humans have inadequate shelter; 1.3 billion people (70 percent female) attempt to live on less than $1 a day — up by 200 million over the past decade; 2 billion have no access to electricity; and 2.6 billion lack basic sanitation.

This misery translates into massive social disintegration. Some 1.2 billion adults are either unemployed or woefully underemployed below a living wage. This is one-third of the world's workforce and the highest percentage since the 1930s. More than 250 million children between 5 and 14 years of age are working as child laborers. Income inequality is rising within and among all nations. The share of global income of the richest one-fifth of the world's people is now estimated to be 74 times that of the poorest one-fifth — a gap that has doubled over the past 30 years. Forbes Magazine estimates that the combined wealth of the 225 richest people in the world now equals the combined annual incomes of the poorest one-half of humanity. The widening social gulfs breed anger, frustration, alienation, anomie and hopelessness.

What is the relevance for those engaged in global business?

An obvious answer is that if they go uncorrected these trends imply greatly increased exposure to external risks of all kinds, and massive constraints on the global "operating space" available for business development. In many parts of the world environmental degradation and growing resource scarcity, together with poverty and population density, are already contributing to economic disruption, forced migrations, ethnic strife, cross-border health crises, famine, fundamentalism, regional conflicts over resource use, weakened states, and even "eco-terrorism."

Such instability adversely affects the investment climate, furthering the downward spiral in socio-economic and environmental decay. Heavily populated swathes of the planet disappear from the strategic "radar screen" for business and market development.

All business — in any form, in any place, at any time — is directly or indirectly, immediately or eventually affected by ecological and socio-economic deterioration wherever this occurs. Business takes place within, and is thus dependent upon, the vital "life support" services provided by the biosphere. Corporate welfare is equally dependent on healthy social systems. Business worlds would cease to thrive without educated citizens, public safety and order, a supply of savings and credit, legal due process, or the observance of rights.

It would thus seem logical for business to protect, maintain and restore the integrity, resilience and productivity of such vital life support services, a premise that leads inexorably to a conception of the moral corporation.

To paraphrase Christian philosopher Albert Schweitzer: "it is good: to preserve, promote and raise to its highest value, life capable of development; it is evil: to destroy, injure, and repress life capable of development. This is the absolute fundamental principle of the moral. A man (business) is ethical only when life, as such, is sacred to (it)."

A model for strategy

The core idea of sustainable development was most influentially defined by the World Commission on Environment and Development as "that which meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs." Hundreds of derivative definitions have followed, and the notion appears set to remain fuzzy, elusive or contestable for some time to come. This is to be expected during the emergent phase of any new, big and generally useful idea. There is broad agreement that ensuring future generations are no worse off than the present one requires the maintenance of welfare-yielding capital endowments. A sustainable society lives off the "income" generated from its stocks of capital, not by depleting these. There are differences of opinion over attempts to specify the exact assumptions, conditions and rules for ensuring development paths that are both fair to different generations and efficient over time.

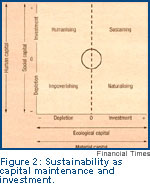

Figure 2 shows a "strong" model of sustainable development. This assumes natural and social capital are complements of, rather than substitutes for, manufactured capital. Different types of capital must be maintained intact separately, for the productivity of each depends on the availability of the others (i.e., the model abandons the conventional neo-classical assumption of near-perfect substitution for different types of capital). We can thus appraise the workings of manufactured capital (i.e., stocks of producer and consumer goods such as factories, buildings, machines, tools, technologies, infrastructure and products) according to their consequences for four types of primary (enabling or limiting) capital:

Figure 2 shows a "strong" model of sustainable development. This assumes natural and social capital are complements of, rather than substitutes for, manufactured capital. Different types of capital must be maintained intact separately, for the productivity of each depends on the availability of the others (i.e., the model abandons the conventional neo-classical assumption of near-perfect substitution for different types of capital). We can thus appraise the workings of manufactured capital (i.e., stocks of producer and consumer goods such as factories, buildings, machines, tools, technologies, infrastructure and products) according to their consequences for four types of primary (enabling or limiting) capital:

- ecological (i.e., renewable, cyclical, biological resources, processes, functions and services)

- material (i.e., non-renewable or geological resources such as mineral ores, fossil fuels, fossil groundwaters)

- human (i.e., people's knowledge, skills, health, nutrition, safety, security, motivation)

- social (i.e., relating to civil society, social cohesion, trust, reciprocity norms, equity, empowerment, freedom of association, orderliness and so forth that facilitate co-ordination and co-operation for mutual benefit).

A society would become increasingly sustainable (boosting its capacity for continuance) as it organizes its economy to invest in and expand existing stores of primary capital (moving to the northeast of the grid). Such restoration lies at the heart of "natural capitalism," according to a book by Paul Hawken, and Amory B. and L. Hunter Lovins.

The two-by-two grid yields four states of society, only one of which is sustainable. The southwest quadrant is the impoverishing zone, where society imprudently "lives" off a vanishing capital base. This is a society that maintains itself only through the exhaustion and dispersion of a one-time inheritance of natural capital (e.g., topsoil, biodiversity, groundwater, fossil fuels, and minerals) with no investment in conservation or replacement. This is a society (too common, sadly, today) that disinvests in its people, especially its children, and permits the forces of mobile economic capital, elite detachment, and special-interest politics to atrophy civic and social communities.

The southeast quadrant of Figure 2 is the zone of naturalizing, where the operations of the economy are increasingly brought into conformity with natural imperatives. This comes at the expense, however, of human and social capital, at least transitionally. Examples might include "eco-inspired" agricultural biotechnology that threatens traditional farmers with redundancy or cleaner automated factories that eliminate assembly and manufacturing jobs. In the absence of alternative sources of sustainable livelihood, these supposedly "environment-friendly" developments could set in motion powerful forces of social decomposition and political upheaval. Naturalizing, in the absence of concomitant attention to the human condition, may be self-defeating.

A similar logic applies to the northwest quadrant of Figure 2, a zone of humanizing, where the operations of the economy are progressively endowed with a human character. This is at the expense, however, of diminishing natural capital. Examples might include the development of housing communities on drained wetlands, or logging which causes deforestation. Jobs or communities constructed on the basis of systemic depletion of natural capital will obviously be unsustainable over the longer term. Humanizing and naturalizing are fundamentally complementary.

This leaves the northeast quadrant as the only genuine sustaining zone. Economic and technological development here are simultaneously people-centered and nature-based. Damage to ecosystems is prevented, biological diversity and productivity are conserved, the entropic physical flow of energy and matter is moderated, and the economy is converted to rely on perpetual resources and resilient technologies. The sustainable society communalizes its civic order and decision-making, democratizes its political and workplace environments, humanizes capital creation and work, and vitalizes human need fulfillment, ensuring sufficiency in meeting basic needs.

These macro-level principles of sustainable development unfold into myriad sub-principles, guidelines, and metrics for application at the micro-level.

The ecologically sustainable enterprise would:- eliminate all harmful discharges into the biosphere;

- use renewable resources like forests, fisheries and fresh water at rates less than or equal to regeneration rates;

- preserve as much biodiversity as it appropriates;

- seek to restore ecosystems to the extent that it has damaged them;

- deplete non-renewable resources such as oil at rates lower than the creation of renewable resource substitutes providing equivalent services;

- continuously reduce risks and hazards;

- dematerialize, substituting information for matter; and

- redesign processes and products into cyclical material flows, thus closing all material loops.

- return to communities where it operates and sells as much as it gains from them;

- include stakeholders affected by its activities in associated planning and decision-making processes;

- ensure no reduction in, and actively promote the observance of, political and civil rights in the domains where it operates;

- widely spread economic opportunities and help to reduce or eliminate unjustified inequalities;

- directly or indirectly ensure no net loss of human capital within its workforces and operating communities;

- cause no net loss of direct and indirect productive employment;

- adequately satisfy the vital needs of its employees and operating communities; and

- work to ensure the fulfillment of the basic needs of humanity prior to serving luxury wants.

Transformational leadership

Sustainable development is an idea whose time has come but it is important to acknowledge the extraordinary barriers that stand in the way of its general acceptance and achievement. These include: mechanistic thinking; conventional wisdom promoting growth; consumption and techno-fixes; institutional structures such as perverse governmental subsidy and tax systems; and the profound forces of inertia compounded by vested interests and denial. I am strongly encouraged by the emergence of a well-informed and visionary set of corporate leaders who have taken up the challenge of orienting their companies to support a sustainable human future. These transformational leaders can be found, for example, in family-led enterprises; entrepreneurial ventures into renewable resources; companies which have learned from public controversies; "culturally programmed" Scandinavian enterprises; and companies getting out of commodity businesses into more knowledge-intensive life sciences.

Large-scale organizational transformation toward sustainability is a long-term and multi-level challenge, entailing a range of reinforcing roles and tasks. Vivid images of sustainable futures must be painted. A sense of stretch must be instilled. Organizational purpose, identity and meaning must be aligned with ecological and social contribution. Leaders must challenge embedded assumptions by asking tough questions: what is our ecological and social footprint? Do customers really need our products, or just their functions or services? Are we focusing on "excessities" or necessities? Are we creating genuine value for society or appropriating value from it? What is our rightful place in the living world?

Implementation must be energized by dramatic changes in management incentives, internal information systems, and external performance reporting. Major in-house learning programs must be mounted to boost awareness, literacy and strategic excitement. Supportive organizational values and ethical principles must be infused. High impact partnerships with other companies and governmental/non-governmental organizations (rf. Relevant links) must be forged. Finally, leaders for sustainability must take on the hard work of lobbying for public policies and institutions that truly work on behalf of a sustainable future.

"Between the idea and the reality, between the conception and the creation, falls the shadow," said T.S. Eliot. The notions of sustainable development and enterprise currently lie in this shadow. The central task of corporate leaders moving into the next century, both through aspiration and inspiration, is to bring them into the light.

Relevant links

SustainAbility Ltd. (www.sustainability.co.uk)

The World Business Council for Sustainable Development (www.wbcsd.org)

Tomorrow: Global Sustainable Business (www.tomorrow-web.com)