This web page is part of the Michigan Today Archive. To see this story in its original context, click here.

February 2006

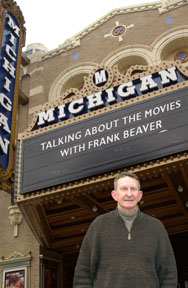

Talking about the movies: Film theory applied: Cowboy "renovation" and Brokeback Mountain with Frank Beaver

When Annie Proulx's rhetorically taut short story Brokeback Mountain was published in 1997, it was immediately recognized as a literary classic. The anguished account of two sexually bonded sheep herders cut to the quick with a force of emotion that belied its slim form. Proulx's gift was in her ability to unmask the abrupt feelings and lingering attachment that left the two simple men crushed by the uncertainties of their longings. It was a heart-wrenching tale much praised for having moved beyond the clichés of Western cowboy storytelling. It came as no surprise to me when I heard that novelist Larry McMurtry was to be one of the executive producers of the film version of Brokeback Mountain and co-author of the screenplay adaptation. In a series of essays published in 1968 in a volume titled In a Narrow Grave: Essays on Texas, McMurtry spoke out about the shortcomings of cowboy folklore. Of particular concern to him was the overriding sentiment for nature that he felt had dominated Western fiction. In one essay he wrote: "Sentimentalists are still fond of saying that nature is the best teacher. I have known many Texans who felt that way and most of them live and die in woeful ignorance. When I lived in the country I noticed no abundance of full men." McMurtry said that the other dominating aspect of the Western genre had been the emphasis on gun fighting, with the hero resorting to violence so that "right may prevail." The tendency toward sentiment and heroic violence was said to have had a "blurring" effect on the portrayal of cowboy realities, resulting in romantic and mythic fiction and diminishing the opportunity for irony and intellectual process in the storytelling. He noted that writers had given little importance to the working cowboy and to domestic issues of life on the ranch and on the trail. In his fiction McMurtry went about the task of reinventing the Western and "renovating" the cowboy. Early novels—Horseman Pass By (1961), Leaving Cheyenne (1963) and The Last Picture Show (1966)—had contemporary settings and incorporated thematic motifs that dealt with initiation, loneliness, alienation and a sense of loss among "urbanized" cowboys. Critics praised McMurtry's fiction for its success in escaping the hold of Western mythology. Most notably, it was the element of irony that signaled McMurtry's departure from the usual treatment of the West in fiction and film. His characters are ambivalent about the land, its people and their own place in it. Sentiment is pushed aside.

Two decades later McMurtry capped his "renovation" fiction with Lonesome Dove (1985), a book that turned the mythology of the Western trail ride upside down. The cowboys who rode with the Hat Creek Cattle Company were vulnerable individuals of uncertain direction. They were often terrified and confused by the trials they faced on the trail, sometimes breaking into tears and going to pieces emotionally. Woodrow Call and Gus McRae, the principal characters, engage in philosophical discussions about what they're doing and why they've done it, and almost never with telling conclusion. The bond between the two men is so great that after Gus's death Call's grief is such that the dead man haunts Call's dreams and his waking hours. In 1989 Lonesome Dove was turned into one of the best television mini-series yet produced. It was notable for its bittersweet tone, its ironies and its avoidance of heightened heroics. Although it's been over a decade since I've seen the television adaptation, I still have vivid memories of those quiet, introspective conversations between Gus and Call. Their debate about whether their lives as human beings who had been "free on the earth" had made them happy reinforced the epic story's ironic contradictions and its attention to mental process. The great achievement of Lonesome Dove was that in re-appropriating the trail ride as the narrative structure of his working cowboy saga, McMurtry simultaneously evoked nostalgia and affection for the genre while pulling back from its "blurring" myths. Annie Proulx's short story, and the movie made from it, present the "renovated" cowboy in the most forward and touching treatment to date. In watching Brokeback Mountain I saw the work of two visionary writers devoted to revealing the complex humanity of the Western cowboy. The result for me was a screen drama that was both beautiful and tragic.

|

|

Michigan Today News-e is a monthly electronic publication for alumni and friends. |

| MToday NewsE | |

|

|

Michigan Today

online alumni magazine

University Record

faculty & staff newspaper

MGoBlue

athletics

News Service

U-M news

Photo Services

U-M photography

University of Michigan

gateway