This web page is part of the Michigan Today Archive. To see this story in its original context, click here.

February 2006 Talking about words: Bassackwards

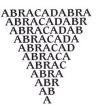

Words are magical, and we love to make magic with them. Some of the magic is highly conventionalized like the abracadabra spoken by the amateur conjurer to fetch an egg from behind a child's ear or a quarter from nowhere. Once upon a time abracadabra was a word to cure illness. The afflicted person—or someone in fear of contagion—shaped the words into a magic pyramid.

Shaping and reshaping words is a way to invest them with power or deprive them of taboo. Dog nab it! takes the three letters of God and leaves behind blasphemy when the g and the d change places. Doggone it! takes the sting out of the Third Commandment too. Evasion is just a way around the deep power of words. Literally, tetragrammaton is any four-letter word, but it usually applies to the four letters that make up the Hebrew word rendered in English as Jehovah or Yahweh. Since it was (and is) forbidden to use this word outside a holy setting, the word tetragrammaton, all by itself, becomes a harmless way to mention the word that was too perilous to write. Word magic is powerful stuff. In Christopher Marlowe's Dr. Faustus, a play performed first about 1589, the doctor's lusts lead him to sell his soul to the devil. But how to get the devil to the table? Not hard for a powerful magician like Faustus.

By this method—rearranging the letters of the tetragrammaton "forward and backward," Faustus summons up a devil and begins to see his wishes fulfilled. Writing Jehovah's name forwards is one solemn thing; writing it backwards and making an anagram out of it is another. Of course, Faustus uses all the methods he's heard about for raising the devil—signs of the Zodiac, for instance, and the chopped-down names of the saints. But the first one he mentions seems to be the one that does the trick. Making magic with other tetragrammatons is everywhere apparent on the University of Michigan campus. Transposing letters of the four-letter taboo words makes for surprising messages on t-shirts: Puck Fenn State, for instance, as a way of denigrating the Nittany Lions. A line of beauty products and designer clothing bears the (unpronounceable) name: Fcuk. Somehow, wearing a taboo word on your shirt or using it to wash your hair is all right, as long as it's written in some way bassackwards. Putting the letters in the wrong order may create magic (as Faustus found). Or it may take the magic out of them. Whichever way, it's magic.

|

|

Michigan Today News-e is a monthly electronic publication for alumni and friends. |

| MToday NewsE | |

|

|

Michigan Today

online alumni magazine

University Record

faculty & staff newspaper

MGoBlue

athletics

News Service

U-M news

Photo Services

U-M photography

University of Michigan

gateway

Written on parchment and hung from one's neck, these words drove away evil. The magic didn't work so well for the physician who provided us the first written information about abracabra: he was put to death in 212 AD by one of the blood-thirsty Roman emperors who had invited him to dinner and then had him killed.

Written on parchment and hung from one's neck, these words drove away evil. The magic didn't work so well for the physician who provided us the first written information about abracabra: he was put to death in 212 AD by one of the blood-thirsty Roman emperors who had invited him to dinner and then had him killed.  Richard W. Bailey is the Fred Newton Scott Collegiate Professor of English. His most recent book is Rogue Scholar: The Sinister Life and Celebrated Death of Edward H. Rulloff, University of Michigan Press, 2003--a biography of an American thief, impostor, murderer and would-be philologist who lived from 1821 to 1871. It was published by the

Richard W. Bailey is the Fred Newton Scott Collegiate Professor of English. His most recent book is Rogue Scholar: The Sinister Life and Celebrated Death of Edward H. Rulloff, University of Michigan Press, 2003--a biography of an American thief, impostor, murderer and would-be philologist who lived from 1821 to 1871. It was published by the