This web page is part of the Michigan Today Archive. To see this story in its original context, click here.

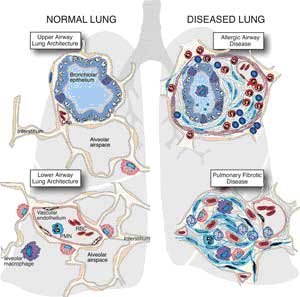

The good, the bad and the deadly.By Sally Pobojewski  “When we’re hurt or seriously ill, our first response is to call a doctor or head for the nearest emergency room. But faster than you can dial 911, the body’s internal emergency response team is already on the scene. Responding instantly to biochemical distress signals from damaged tissue, specialized cells and proteins start to seal off the injured area, destroy damaged tissue and kill invading bacteria. It’s called the inflammatory response, and the pain, heat, swelling and redness we associate with it are signs that it’s isolating the injury or infection to protect healthy areas of the body. In its zeal to protect the body, the inflammatory response will destroy as much tissue as necessary to accomplish this goal. Inflammation is the body’s first line of defense against injury and infection, but it’s a double-edged sword. An out-of-control inflammatory response can destroy healthy tissue and cause more damage than the original problem. Left unchecked, a hyperactive inflammatory response can continue attacking healthy tissue. Keeping it under control means the immune system must maintain a balance between fanning the flames of inflammation and cooling it down. Dr. Peter A. Ward, the Medical School’s Godfrey D. Stobbe Professor of Pathology, has devoted his career to understanding the interactions among genes, cells and signaling molecules involved in this delicate balancing act. “When immune systems go awry, virtually without exception the problem begins with the triggering of a strong inflammatory response,” Ward says. “All autoimmune diseases —such as rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, lupus or multiple sclerosis —are diseases in which the inflammatory response is unregulated, excessive and out of control. So understanding the inflammatory system from A to Z will have huge applications in any number of diseases or clinical situations.” Like everything else in the human immune system, the inflammatory response is controlled by an incredibly complicated communications network made up of multiple cells, cascading signal pathways and feedback loops. One of the most important discoveries made by Ward and other scientists over the last 20 years has been the identification of a network of natural anti-inflammatory mediators, produced by the immune system to offset activity of pro-inflammatory agents. This network of “chill out” signals keeps inflammation focused on the area of local infection or injury, and prevents a runaway response that can spread through the body. Four years ago, Ward expanded his research on the inflammatory response to include what he calls “the enigma of sepsis,” the most dramatic example of an out-of-control inflammatory response. In the United States this year, more than 600,000 Americans will experience the deadly combination of symptoms—high fever, elevated white blood cell count, rapid heartbeat, falling blood pressure and confusion—that physicians call sepsis. Patients at highest risk are those recovering from traumatic injuries or surgery, and those with serious infections or chronic diseases. Unless it’s caught early, sepsis can kill a formerly healthy adult in just a few days. Sepsis kills more people each year than breast cancer and prostate cancer combined. What Ward has found so far is that the inflammatory signaling system in laboratory rats with sepsis is hyperactive, and the rats have abnormally high amounts of a pro-inflammatory protein called C5a in their bloodstream. When the animals are given drugs to block C5a’s effects, their survival rates improve substantially. In recent research, Ward and his team discovered that, once C5a is in the bloodstream, it blocks all the receptors on circulating neutrophils—preventing them from attacking invading bacteria and effectively paralyzing the immune response. “We hope to find a way to block the activity of C5a in animals with sepsis,” Ward says. “If we are successful, it could be an effective therapeutic intervention in humans. We also are investigating how to measure the C5a receptor content of neutrophils. This could be the basis of an early diagnostic test for sepsis to help physicians identify patients who need immediate aggressive treatment.” Full version of this story available at: http://www.medicineatmichigan.org/magazine/2005/spring/lungs/default.asp

|

|

Michigan Today News-e is a monthly electronic publication for alumni and friends. |

| MToday NewsE | |

|

|

Michigan Today

online alumni magazine

University Record

faculty & staff newspaper

MGoBlue

athletics

News Service

U-M news

Photo Services

U-M photography

University of Michigan

gateway