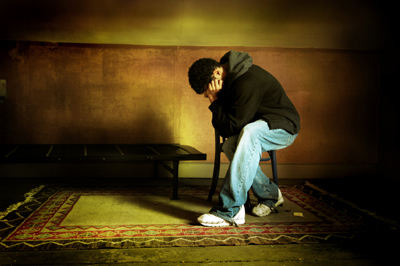

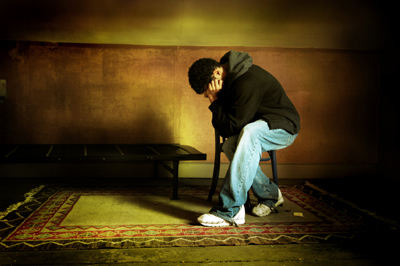

The Quiet Giant

U-M researchers pursue clinical depression, one of the top five causes of disability on our planet.

By Leslie Stainton

Findings Magazine

School of Public Health

Major depression, once an ordeal suffered alone in private, and often in shame, is now a significant focus of public health research. Some would argue it's the major public health issue of this century. As the stigma recedes and research increases, U-M scientists are hopeful for a better future for depression sufferers.

Like diabetes and cardiovascular disease, depression is a “biological illness that is linked to events of living,” says John Greden M.D., executive director of the U-M's trailblazing Depression Center. Although their underlying causes vary, all depressive illnesses are brain disorders, and all have a biological foundation, Greden says. “It has taken people a long time to recognize that, which is part of the stigma.”

Between 18 and 20 million Americans—17 percent of the population—suffer from depression, women more than men. Worldwide, depressive illnesses account for 75 to 85 percent of all suicides. Clinical depression is one of the top five leading causes of disability on our planet. Together with bipolar disorder, or manic depression, it is costlier and more burdensome than any other ailment except cardiovascular disease.

A common thread in illness

“More than any other health condition, depression represents a person's overall well-being,” says assistant professor Daniel Eisenberg, of the school of public health. “In that sense, treating depression gets directly at public health's most important outcome.”

“Depression can contribute to obesity,” explains Kyle Grazier, professor of health management and policy in the school of public health. “It's hard to stop smoking when you're depressed. Depression keeps people out of the workplace in huge numbers, reduces productivity at school and work, and has tremendous ramifications for our economy.” People who suffer from depression are nearly 28 times more likely to miss work because of emotional disability.

“The relationship between depression and chronic illnesses such as asthma, diabetes, and heart disease is not well understood,” says Noreen Clark, director of the Center for Research on Managing Chronic Disease at the school of public health. “But there is no question that the presence of depression makes the management of any disease more problematic.”

Not long ago, society viewed depression as a moral weakness, not a physical disease, and people kept it a secret. Insurers paid little or nothing for treatment. Combined, these two factors—stigma and cost—kept people out of care, says Grazier, who is currently examining the integration of depression and primary care through studies funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan.

Just last year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention acknowledged that depression is a risk factor “for such chronic illnesses as hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes, and can adversely affect the course and management of these conditions.” The CDC called for public health agencies to “incorporate mental health promotion into chronic disease prevention efforts.”

Depression also underscores social and ethnic differences in health. African-American women, for example, have a significantly lower depression rate than white women, and overall, fewer blacks than whites commit suicide. At the same time, African Americans are less likely than whites to seek outpatient care for depression.

Depression is “one of the largest and most pervasive racial disparities,” in health care, according to Harold W. Neighbors, a professor of health behavior and health education and director of the U-M Center for Research on Ethnicity, Culture and Health. African Americans are far less likely than white Americans to get outpatient care for depression—“regardless of income, education, or insurance coverage.”

Sandro Galea, an associate professor of epidemiology has found that residents of so-called “bad” neighborhoods—neighborhoods with poor physical infrastructure, indoors and out, and high levels of income inequality—are more likely to suffer depression, “independent of individual characteristics,” Galea emphasizes.

Galea has also studied how depression rates spike in the wake of both natural and manmade disasters. Typically, the prevalence of depression after a major disaster is about twice the baseline “of what you’d expect,” says Galea, who co-directs the Disaster Research Education and Mentoring Center, a collaboration between the University of Michigan and the Medical University of South Carolina.

In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, Galea expects to see heightened rates of depression along the Gulf Coast, particularly because so many people were displaced and therefore lost the “immensely protective” force of social networks and supports.

A chronic public health issue

Together, all of these facts argue for depression as a major public health issue. And after centuries of misconception, depression is at last losing its stigma. “Everybody has a relative or a friend or a spouse or a coworker who has this,” says the Depression Center's Greden, who is also chair of the department of psychiatry in the u-m medical school. “They understand it is an illness—they get it.”

In the past five years health officials have begun to view depression as a chronic disease, and it now turns up in the nation's large disease-management programs. The World Health Organization lists depression as one of the most disabling disorders in the world.

While the roots of depression remain elusive, scientists are actively trying to understand its genetic sources. SPH and Depression Center biostatistician Sebastian Zöllner is hopeful that someday we'll know enough about DNA's influence on depression to be able to better diagnose and treat the disease. What is clear is that first-degree relatives of people with major depression are themselves at two to three times greater risk for depression.

Neurobiologists are finding that the chemistry of the brain is changed by depression. “Most of the recent findings suggest that if you can successfully treat depression, you can do some restoration of these neuronal degenerative changes,” Greden says.

The U-M Depression Center, currently nearing completion of its new home northeast of campus, is the nation's first comprehensive center devoted to tying together all of the research, treatment, education, and public policy on depressive illness.

“Prevention—real prevention—is a foundation of our vision,” says Greden. “We have much to do to achieve that dream, but no other long-term goal is acceptable.” Greden is hopeful that the U-M Depression Center, which was created in 2001, will become part of a national network of such centers, and he's optimistic that within 10 to 15 years, research advances will yield even better treatments.

Before psychiatrists and other specialists can begin thinking about treating the disorder, it's paramount that primary care practitioners be trained to recognize the symptoms of depression, Grazier says.

“Our hypothesis is that the only way to treat depression is by integrating care—having primary-care physicians work with mental health specialists,” Grazier explains. “The vast majority of people with depression—some estimates say over 75 percent—never seek out a mental health specialist but instead seek care through their primary care practitioner.”

Grazier thinks it critical that scientists, policymakers, advocates, and clinicians do their utmost to enable “healthy, fulfilling lives for those stricken with depression.” She speaks for many when she adds, “I really think this disease gets at the soul of public health.”

|