|

Adaptations and Hollywood Films |

In September 1932 Paramount bought the film rights to Sanctuary. The book had become quite popular, perhaps because a superficial reading gave the reader a sensationalistic tale full of horror and suspense and sexual abnormalities. A closer reading, of course, offered thought-provoking implications concerning the nature of terror, injustice, and responsibility, to oneself as well as to others.

The first film version, entitled "The Story of Temple Drake," was released in May 1933. It toned-down the more deviant behaviors and included a completely new scene at the end, but did manage to retain most of the suspense of the original story. The screenplay, written by Oliver Garrett, changed the plot in certain key elements, especially with regard to Temple. In the novel Temple commits perjury, causing an innocent man to be found guilty of her rape and the murder of Tommy, the mentally retarded handy man who had tried to protect her. In the film, Temple kills Trigger (Popeye in the novel), and her testimony at the trial suggests the beginning of her moral regeneration, a process that Faulkner explores in the sequel, "Requiem for a Nun."

The poster advertises the 1961 Twentieth Century-Fox version

of Sanctuary in which the plots for the earlier version and "Requiem" are

merged into a single story. The film was directed by Tony Richardson,

the same man who had staged Requiem in London, and produced by Richard

Zanuck, the son of Darryl Zanuck, for whom Faulkner had worked in the 1930s.

Requiem for a Nun is another of Faulkner's analyses of the implications of evil. Not published until 1951 it presents Temple Drake eight years after the events chronicled in Sanctuary. She is now a wife and mother of two small children. Her husband is Gowan Stevens, the drunken playboy who deserted her, leaving her in the hands of the hoodlums at the Old Frenchman's place. The new story tells of her guilt, her attempt to escape by running off with her blackmailer-lover, the murder of her six-month-old daughter, and her final confrontation with her past. It is a story describing how a person might attain redemption, but only after suffering and self-sacrifice. The nun is Nancy Mannigoe, a black woman, a prostitute, and a dope addict who is convicted of the baby's murder, but who murders in order to save the child from the "debased and perilous underworld existence" it would lead when Temple chooses life with her new lover.

Faulkner wrote the novel in the form of a three-act play, each act introduced

by a narrative "preamble" focusing on the building in which much of the

dramatic action occurs: the courthouse in Jefferson, the state capitol

building in Jackson, and the jail in Jefferson. All three structures

are associated with the preservation of law and order in a civilized society,

whereas Temple"s degenerative behavior is just the reverse.

|

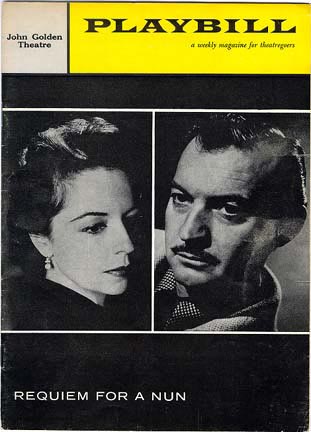

William Faulkner and Ruth Ford. Requiem for a Nun. [Playbill.] New York: Golden Theatre, [1959].Actress Ruth Ford, a long-time Faulkner family friend, believed that Requiem for a Nun could be effectively transferred to the stage. She made some minor changes and condensed some of the longer passages of dialogue. Although it failed in America, it was successful in London and in other European countries. It received fairly enthusiastic notices and played to packed houses for all of its one-month, limited London engagement. New York reviews were less favorable, most critics complaining that there was too much talk and too little action. The Broadway production closed after forty-three performances. |

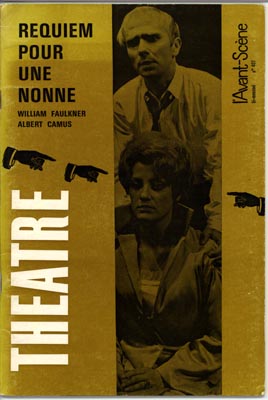

William Faulkner and Ruth Ford. Requiem pour une Nonne. Translated by Albert Camus. [Paris] : L'Avant-Scegrave;ne, no. 407, [1968].The play was particularly successful when it played at the Théâtre des Mathurins in Paris in 1956. It was restaged in 1968 at the Comédie de l’Ouest at which time this issue of L’Avant-Scène was published. In addition to publishing the text of the play, there are stills from the production, a short essay by Camus (entitled “L’Humaine Grandeur du Requiem”), notes by the directors George Goubert and Guy Parigot, and excerpts from reviews that appeared in 1968. |

|

See first two pages of screenplay. |

Irving Ravetch and Harriet Frank, Jr. The Long, Hot Summer. Screenplay adapted from a group of stories by William Faulkner. [N.p.]: Twentieth Century-Fox Film Corporation, 1957 August 26.In 1955 Jerry Wald, for whom Faulkner had worked at Warner Brothers, optioned the movie rights to The Hamlet. Wald changed the name so as not to confuse this one "with that other Hamlet," and decided that the movie should be shot in widescreen and color, the first Faulkner film to appear so. The husband and wife team of Ravetch and Frank borrowed the title from section three of the novel, but drew most of the script from the other sections: "Flem," "Eula," and "The Peasants." They used the episodes of the barn burning, the spotted horses, and the hidden treasure, and then wrote their own script to tie these scenes together. Although the Snopes character (Ben Quick in the movie) is less cruel than in the novel and the end of the film allows the bad guy, Snopes, to get the money, a good name, and the girl, the film stands alone on its own merits and became a box-office hit in 1958. |

In response to the success of the film, Signet Books issued the third

section of The Hamlet in this slim, 35-cent paperback. The title

of the original Book Three was "The Long Summer." Signet carefully

inserted 'hot' to match the title of the movie and selected one of the

"hotter" scenes for the cover illustration.

| The Twentieth Century-Fox's Exhibitor's Campaign Manual, for The Long Hot Summer offered suggestions to theatre owners on ways to advertise this "coming attraction." |

Faulkner spent long months and long years in Hollywood, making himself use his time and talent on work he believed was beneath him just so he could pay his bills. Usually the writing was what he considered "hack work." But in early 1943, film director Howard Hawks asked him for help in preparing a script for Hemingway's novel, To Have and Have Not. Hawks said that when Hemingway had refused his offer to work for him in Hollywood, he said "I'll take your worst book and make a movie out of it, and you'll make money on it." The novel Hawks selected was To Have and Have Not. Hemingway sold him the screen rights and Hawks went to work, using Warner Brothers for financing and facilities.

The first screenplay was written by veteran scriptwriter Jules Furthman whose credits included "Treasure Island" and "Mutiny on the Bounty." It was a 151-page screenplay that Warner Brothers was "urged" not to film because it featured smuggling and insurrection that reflected badly on Cuba and the Batista regime. Cuba and the U.S. were allies in the war effort and the U.S. was unwilling to do anything to endanger that relationship. Thus, Faulkner had a full shooting script from which to work, but which required an entire reshaping.

Faulkner suggested changing the location to Martinique and developing a political interest that would be the conflict between the Free French and the Vichy government. He also created the character "Slim," based on two separate women in the previous screenplay. Scholar Bruce F. Kawin says that Faulkner was little motivated to change Hemingway's material simply because it was Hemingway. He was more interested in the political aspects of the script, his anti-Vichy sentiments, and the characterization of the Resistance fighters, particularly the women.

When the film was released it was quite a success, becoming one of the thirty top-grossing pictures of 1944.

|

William Faulkner. The Reivers. Cinema Center Films Pressbook. New York: Cinema Center Films, 1969.The novel was published one month before Faulkner's death. The reviews were mostly favorable, comparing it to other adventure stories for boys and recognizing that it is fundamentally an amusing tale about a young man's initiation into adult life. It was selected as the Book-of-the-Month Club publication for July. On the basis of this reception, National General Pictures purchased the filming rights and hired the writing team of Irving Ravetch and Harriet Frank to prepare the screenplay. (They had also written the scripts for "The Long Hot Summer" and "The Sound and the Fury"). The film was not released until 1969, but when it finally appeared it was a success. Ravetch and Frank were able to "keep faith with the novelist," and one reviewer said that the picture is climaxed with "the damnedest, most exciting horse race anyone ever saw." It has been placed with "Intruder in the Dust" and "Tomorrow" (based on a short story of the same name) as the best film adaptations of Faulkner's work. |

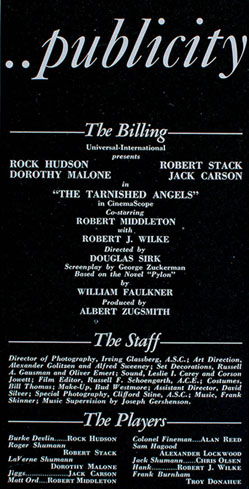

William Faulkner. Pylon // The Tarnished Angels. Showman's Manual. [N.p.]: Universal International, 1957.While most critics consider Pylon to be Faulkner's most flawed novel ("unnecessary horror and violence," "unintelligible descriptive passages," an "inconceivable climax"), Faulkner himself is reported to have considered The Tarnished Angels (1957) the best screen adaptation of his work. This may have been because director Douglas Sirk was interested in making a movie emphasizing returning World War II soldiers who were completely at a loss, drifting rootlessly without a home, without genealogy. Scholar Michael Stern says that Sirk saw the characters in Pylon as wandering on the outside of life "in their futile circling of the [racing] pylons." In addition, the "aesthetic desperation of the prose itself" gave Sirk the basis on which to create a film about postwar despair. The screenplay written by George Zuckerman, combined with Sirk's vision, produced a movie that Faulkner felt was better than the original novel. This "Showman's Manual" offers posters and press releases that can be used in promoting the film. |

|