This web page is part of the Michigan Today Archive. To see this story in its original context, click here.

Talking About WordsWith Prof. Richard W. BaileyEating crow, hot-dogging it and other animal metaphors quick and dead.

English-speaking breatharians face a further obstacle: Our language is designed for carnivores and, everywhere we look, we discover the traces of meat-eating. Eating crow is accepting humiliation. Chow (and the verb chow down) comes straight into American English from the China trade. It means, as a California newspaper of 1856 explained, “something good to eat.” So a chow hound is doubly a dog since the food eaten comes metaphorically from the edible Chinese dog, the chow chow, and the eager eating from a famished beagle or blue-tick. Hot dog (a noun to describe a cocksure young man) and the hot dog (an adjective for something pleasant or exciting) were recorded in American college slang at almost the same time—the former at Yale and the latter at Michigan, both in the 1890s. (At the University in 1896, a student reported that there were some hot dog drawings available.) Not long after that we got hot dog! the equivalent of “Bravo!”—and its companions: hot doggies! and hot diggety dog! Nowadays aviators, surfers, snowboarders and all manner of athletes attract attention by hot-dogging, though these verbal meanings came much later. (Somewhere in this barking collection of words come the wiener or frankfurter. Examples of eating hot dogs come earlier than these meanings, and in the 1870s it was common for people to frequent the hot-dog parlors of New York. It remains to be seen how the sausage made a metaphor for the sassy and smart.) Greedy people wolf down food or pig out. In The Merry Wives of Windsor, Shakespeare gave us the expression, “The world's mine oyster” for having boundless opportunities, having a juicy delicacy to slurp down. Animals are not just the eating or the eaten, of course. Animals are everywhere. “Don't have a cow, man,” admonishes Bart Simpson. He might as well have said go bananas, but Bart's an animal guy. People flounder around indecisively, weasel out of obligations, horse around having fun, squirrel away their savings, beef up their resumé, chicken out when courage fails, grouse about their boss, beaver away at their job, outfox the competition. Of course some of these expressions just look like animals. The bum steer (bad advice) is probably not bovine, any more than we should expect quacking in duck down or duck out. But once these words come to our attention, we want the animals to come alive.

We imagine animals. Is there a bison in the person who is buffaloed by a problem? Do dances like the mamba and the bunny hug actually resemble the behavior of the creatures for which they seem to be named? Is there a baby deer hovering around the person who fawns on her best friend or a tropical bird squawking in the guy who parrots the ideas of others? Some of these metaphors we can be pretty sure about if we've seen the beast involved. Clam up makes sense, but does the mullet “bad hair style” have something to do with the fish? Bear hug, yes, but have a gander, no. People can be catty or turkeys or gorillas or coltish or skunks. Do animals come to mind with equal vividness? Go bats and buck naked are not very obviously connected with animals at all. Everybody has a different piece of the language and a different set of associations and imaginings. Some of these animals are quick, some dead. They are all metaphors. (Crow image on front page from quilt at http://www.joyfield.net)

|

|

Michigan Today News-e is a monthly electronic publication for alumni

and friends. |

| MToday NewsE | |

|

|

Michigan Today

online alumni magazine

University Record

faculty & staff newspaper

MGoBlue

athletics

News Service

U-M news

Photo Services

U-M photography

University of Michigan

gateway

|

• Maps |

A

spiritual discipline known as breatharianism invites

its adherents to eat only air. Vegetarians eat vegetables. Fruitarians eat

fruit. Breatharians may be forced to eat solid food sometimes but

only because air pollution interferes with the assimilation of

the four gasses fundamental to life: hydrogen, oxygen, carbon dioxide

and nitrogen. In a better, cleaner world, breatharians could thrive

solely on inhaling and exhaling.

A

spiritual discipline known as breatharianism invites

its adherents to eat only air. Vegetarians eat vegetables. Fruitarians eat

fruit. Breatharians may be forced to eat solid food sometimes but

only because air pollution interferes with the assimilation of

the four gasses fundamental to life: hydrogen, oxygen, carbon dioxide

and nitrogen. In a better, cleaner world, breatharians could thrive

solely on inhaling and exhaling.

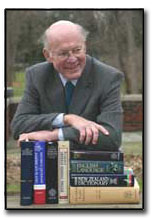

Richard

W. Bailey is the Fred Newton Scott Collegiate Professor

of English. His most recent book is Rogue Scholar:

The Sinister Life and Celebrated Death of Edward H. Rulloff,

University of Michigan Press, 2003—a biography of an

American thief, impostor, murderer and would-be philologist who

lived from 1821 to 1871. It was published by the

Richard

W. Bailey is the Fred Newton Scott Collegiate Professor

of English. His most recent book is Rogue Scholar:

The Sinister Life and Celebrated Death of Edward H. Rulloff,

University of Michigan Press, 2003—a biography of an

American thief, impostor, murderer and would-be philologist who

lived from 1821 to 1871. It was published by the